What can neuroscience teach us about evil?

Not much. At least, that’s what I think. Ron Rosenbaum discusses the question at length in a thorough and thoroughly interesting piece in Slate. Rosenbaum’s discussion confirms my impression that neuroscientists think the ability to fabricate colorful and misleading technicolor pictures of brains license them to philosophize with impunity. Here’s how Rosenbaum begins:

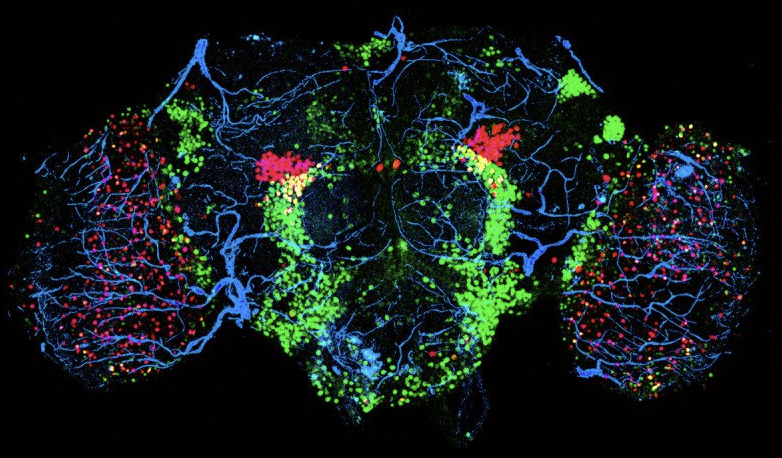

Is evil over? Has science finally driven a stake through its dark heart? Or at least emptied the word of useful meaning, reduced the notion of a numinous nonmaterial malevolent force to a glitch in a tangled cluster of neurons, the brain?

Yes, according to many neuroscientists, who are emerging as the new high priests of the secrets of the psyche, explainers of human behavior in general. … They argue that the time has come to replace such metaphysical terms with physical explanations—malfunctions or malformations in the brain.

Rosenbaum goes on to talk a bit about free will, and some cheeky neuroscientists think they’ve disproved that, too.

All this debunking stuff is based on a very questionable premise: that claims about evil or free will are implicit claims about the way the brain functions. But are they? I think not. You can’t disprove the existence of evil or free will by looking at brains if free will and evil aren’t neurological phenomena.

The view that free will and determinism are incompatible with moral responsibility is called, sensibly enough, incompatibilism. Many folks — and I think some of them are neuroscientists — simply assume that our intuitive, everyday conception of free will is incompatibilist. Thus, if we peek at the brain and find that the springs of action are determined by forces independent of the will, the incompatibilist will declare free will debunked. But I don’t find incompatibilism intuitive at all. Experimental work on intuitions about free will show that I’m not the only one. Indeed, recent research suggests that whether or not you have compatibilist or incompatibilist intuitions about free will depends on how extraverted you are, lending some credence to Nietzsche’s view that our philosophical commitments reflect our personal dispositions. Anyway, it may be that when someone infers the non-existence of free will (or evil) from a brain scan, they tell us more about themselves than about free will.

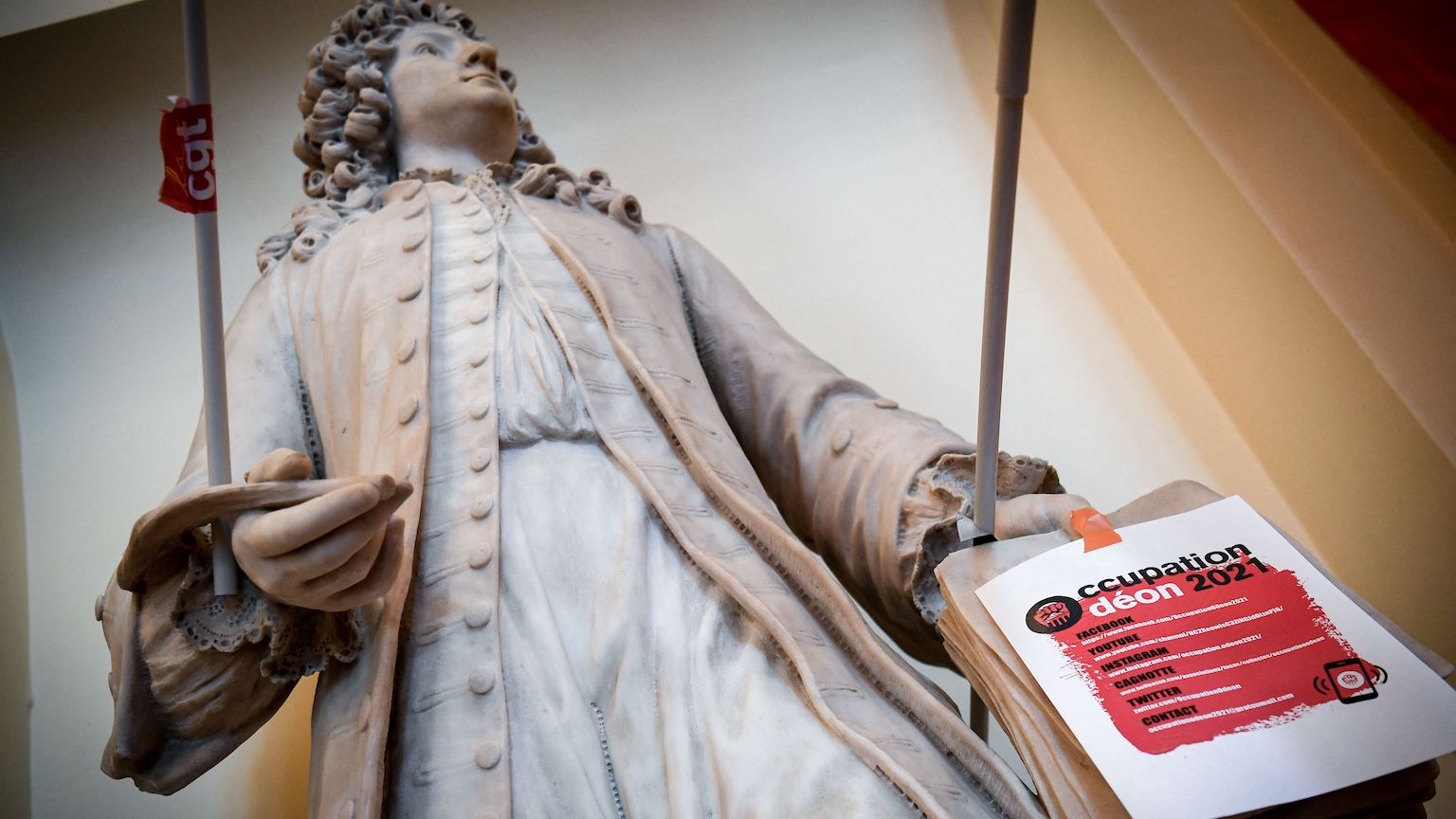

About evil specifically, it seems obvious that people with perfectly normal brains do evil all the time. The interesting empirical question about evil is not whether or not there is any. Anyone who doubts it just confused. For the life of me I can’t see what anything about the brain has to do with the evil of chattel slavery, the brutality of colonial occupation and dispossession, the Holocaust, the Cultural Revolution, etc., etc. Rosenbaum gets it right when he says “Evil does not necessarily inhere in some wiring diagram within the brain. Evil may inhere in bad ideas, particularly when they’re dressed up as scientific (as Hitler did with his ‘scientific racism’).” The interesting empirical question is how it is that people who are not in the least lacking in empathy or disposed to psychopathy can, in the right circumstances, find themselves quite ready and willing to torture, kill, and humiliate other human beings — to do evil.